PROJECTS

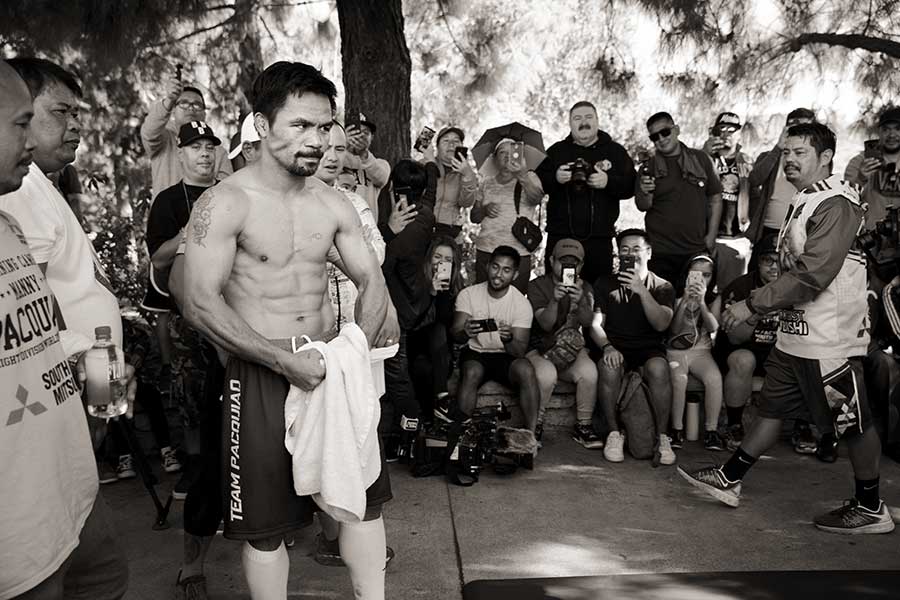

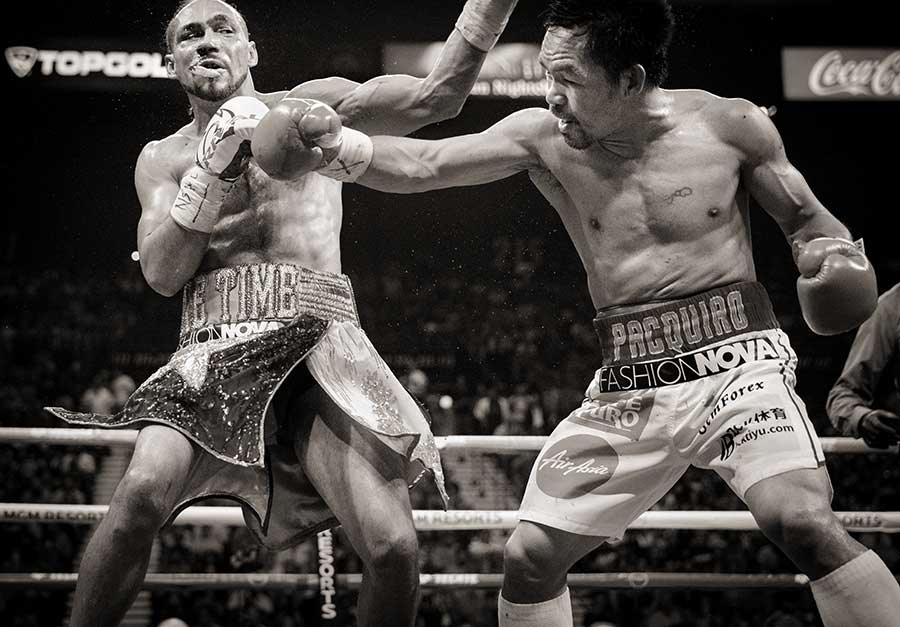

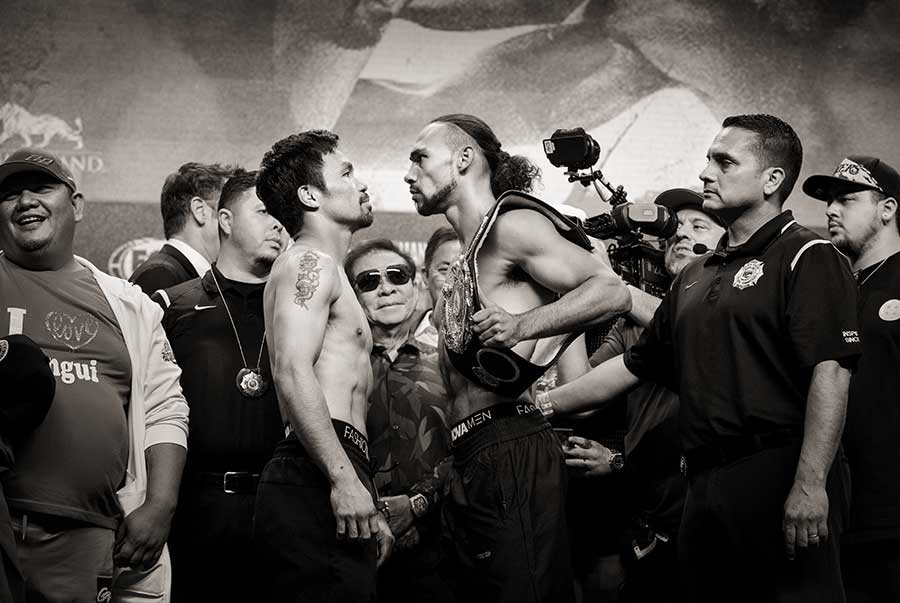

Manny Pacquiao: The man, the boxer, the Senator

Pacquiao’s life is like scripture in the Philippines. It is an argument against limits, a source of pride amid despair, and hope amid hopelessness. His story is so well-known, so ingrained in the minds of the Filipino people, that it long ago became a commodity. He is a vessel into which everyone, regardless of circumstance, can pour their visions of a country and its people. He is the first boxer to win 12 titles in eight weight classes and a man who has parlayed his reputation as the champion of his people into a political career that earned him Duterte’s imprimatur as his chosen successor.

How did this happen? How did the boy who grew up in a homemade hut with a dirt floor and a coconut-leaf roof, who claims to have made his way through unimaginable deprivation by adhering to his mother’s commandments — don’t beg; don’t steal — become this man, one of the Philippines’ 24 senators, protected by heavy artillery as he is escorted across town to a glass-and-steel mansion? He is a symbol of the possible, and his utility is boundless. The rich and powerful, the poor and desperate — they can all find what they want or need in this man and his story.

It is a tribute.

It is a warning.

View the ESPN story by Tim Keown.

Self Immolation in Iraq

“I thought, this is my death,” said Iman Eaziden Bakr, 17. “I felt like a chicken being roasted. I will never forget the torture of my skin. It was so painful—as if my insides were being exposed.” Ms. Bakr poured kerosene on her body and set herself on fire hoping that her act of self-sacrifice would bring peace to her contentious family. But her self immolation was futile, she said. And now she lives with the painful scars.

We’ve all seen the images from the war in Iraq: wounded soldiers, grieving widows and dead Iraqis. What most of us haven’t seen are the faces and charred bodies of the women who are dying – literally – to be set free.

In growing numbers, women and girls, some as young as 13, are immolating themselves. Almost five years after the war in Iraq began, these women live out horrific nightmares behind walls of hopelessness and despair.

“I thought, ‘This is my death,’” said Iman Eaziden Bakr, 17, who lives in Iraqi Kurdistan. “I felt like a chicken being roasted. I will never forget the torture of my skin. It was so painful – as if my insides were being exposed.”

Since my photographs were published in The Dallas Morning News, many have quietly confessed to me that they had never heard the word self-immolation, much less knew that there are thousands of women setting themselves on fire each year.

As new social and economic pressures collide with patriarchal culture and traditions in the newly prosperous region of northern Iraq, Kurdish women still exert little control over their lives. Those who treat their injuries struggle to describe a mental malaise where women see little hope for their future and are driven to kill themselves.

I traveled to Iraqi Kurdistan in September and October of 2007, photographing despondent pregnant women, young brides and teenagers. Their once luminous skin had been charred to a raw and bloody pulp.

The smell was inescapable – human life being extinguished, joy obliterated.

The motives behind the self-immolation varied widely: a dispute with a new stepmother, fear of domestic violence, a spat over a cell phone. But underlying each woman’s reasons was a deep sense of futility in life, the feeling that she would never fully control her own existence.

These women’s lives are negotiated from their fathers to their husbands, and eventually to their sons. Despite their inferior status, they are ironically saddled with the burden of their family’s honor hanging on their every move. They are controlled by a collective society that dictates their inferiority – stripping them of their humanity and leaving them profoundly vulnerable.

Even as scores of women in the Middle East and Central Asia are killed or, at best, disfigured for life, few accurate statistics are available at the international level. In the region of Iraqi Kurdistan, 36 women immolated themselves in 2005, 133 in 2006 and more than 300 in 2007, according to Kurdistan’s Human Rights Ministry. Yet the area’s hospital statistics show thousands of women committing suicide by fire in recent years.

This is a story that is quiet and desperate, an issue overlooked by apathetic governments too embarrassed by the facts. It’s a story revealed only in the recesses of hospitals and by neighbors who feel guilty about their inability to help.

Sadly, the women who survive are often rejected by their husbands and shunned by their own families. And the cycle of misery continues.

These images, created only with the explicit permission of each woman, raise awareness about an issue that, while tragic and dire, worsens each year in complicit silence. As I gained their trust over several weeks, listening and being touched by their plight, I felt a responsibility to give them a voice. Most of them would not recover from their injuries.

Gallery